Gather ‘round and let me tell you a bedtime story…a Deathbedtime story, that is.

I’ve been thinking about the notion of a good death since being present at the bedside of a client who chose to ingest life-ending meds not long ago.

And about how sometimes the whole your day, your way promise can get muddled, the least of which is because the choice-based proposition of dying on one’s own terms is already compromised. Because who willingly chooses cancer, COPD, ALS, heart failure, or umpteen other serious illnesses?

But we hope it will be so — good and choice-based, that is. We want for those making this choice to choose the date, to have the first say on what they want and don’t want on the day-of. I’m talking about who they would want present that day, the room itself and how it might be staged (music, flowers, photographs), and of course, the method of ingestion, assuming a choice is still available to them.

As a ceremonialist, I walk a fine line of having to leave so much of myself at the door when I’m present for families as a Medical Aid in Dying (MAiD) volunteer, especially those who have a hard time with civility. I don’t get to know much about a family system when I first walk into a space, but there is much to be gleaned from the space between people.

I so often wish it was mandatory that families be made to adhere to a basic code of ethics at the deathbed, like say, attending some kind of training workshop, even as I know I colossally failed to be on my best behavior during my father’s dying time.

Death is a motherfucker infamous for bringing out the worst in families. This I know from my last/first responder work as a funeral celebrant who’s the one who often takes the first blows of grief in those hours and days after. One time I had a widow go off sideways on me – her grief needed a human punching bag. I drove home shellshocked and feeling covered in spew. I think about her sometimes and wonder if she’s since found a way to compost her grief into healthier ways of being.

Grief-phobic folks are the ones I’m most watchful for in my MAiD work. It’s important for me to raise my antennae like a giant tuning fork so I can attune myself to the potential perils. I don’t want to have to wear padding or armor, don a Hazmat suit, or bring my lawyer. I’m just an unpaid community helper showing up one of the hardest days a family has ever had to experience, to help lift some of the burden and to undertake tasks many/most would deem unimaginable.

Messiness as a Silent Co-Morbidity.

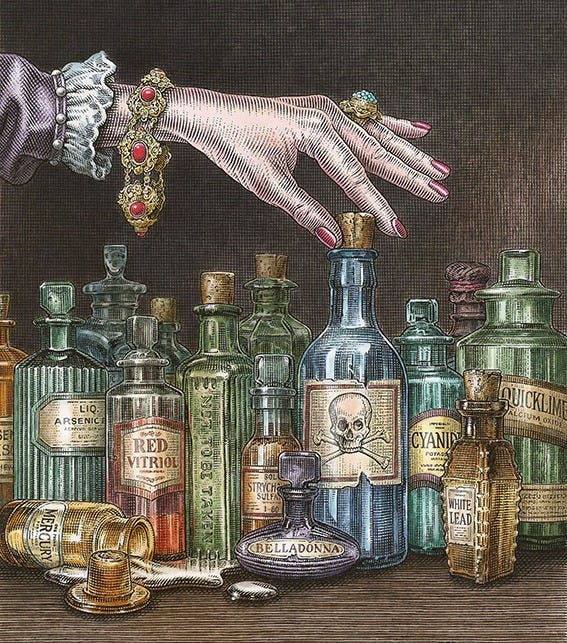

Never mind that I can sometimes be seen as a grim reaper. “I gotta go,” I told my daughter on the phone, just as I was pulling up to the house of a lovely client recently. “OK, Mom – you go kill somebody.” I get that from close friends and family alike – the kind of morbid humor that reads like a badly-explained profession. Some six-word story about being the one who mixes the poisonous beverage to then hand to the person to consume as their last cocktail. Mrs. Reaper at the Bedside bearing Arsenic and wearing Lace while singing, a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down!

“I don’t know how you can do it,” people tell me and there are days, like this aforementioned one, when I’ve wondered the same thing in retrospect. And to be honest, don’t many of us wonder about the careers and avocations of those around us, and how they “do it”?

All this client wanted was a lit candle in their dying hour, but that wish was kyboshed by a significant other. And then to have to ingest two full ounces of a horrid tasting medicine, when swallowing abilities were already compromised. And then to be yelled at and berated by their partner or ex-partner maybe (who was worried their person hadn’t consumed enough) in that penultimate minute of consciousness before the life-ending coma.

Thankfully, this person died 20 minutes later. I say thankfully, because I’m sure that if they could speak in that last minute, their words would have sounded like fuck you to the angry other at the bedside, whose dark cloud of grief and need to micro-manage it all was an unwelcome contaminate. But control keeps grief at bay, right? Right?

The medical aid with this person’s death was amplified by the fact that the spouse in question was a retired medical professional. All discussion and processing of what was happening became clinical. It was the only way they knew to be present to it all. This isn’t the first time I’ve observed this with medical field peeps at a planned death. Each time I witness the funkiness of it, I’m reminded how fervently I wish grief and death literacy could be an entire year of study in med school.

What I’m saying is that for all the beauty (picture a beautifully set room, floral arrangements galore, a favorite song on loop, a gorgeous big dog knowing he was about to step up to as chief grief coach, a bereaved sibling, and two adult children lending a gentle presence while loving on their dying parent and taking up the slimmest trace of space that day), there was another kind of psychical poison that rendered this death with dignity mildly undignified.

And yet, there were glimmers I will take away from it all. This person clamping down on their straw, dying on their own terms, like a stubborn dog with a bone, as if to say, yell at me all you want but I will drink only the barest minimum of this vile concoction.

And so, I return back to the notion of a good death.

I want to make up that Andrea Gibson had a good death, as evidenced by their wife, Megan Falley’s account as well as Tig’s Notaro’s words in the Anderson Cooper podcast chat below. But even then, who’s to say? Who gets to define the good death? Those witnessing, the dying person, the Angel of Death afterlife committee, or a combination thereof?

Learning to Walk Each Other Home, Breath by Breath.

Just as we might be prone to vilify those who of us who do medical aid in dying work, it’s tempting, as Tig and Anderson do, to want to fetishize the work of death doulas. When death is good, there’s nothing like it. But when the family system is messy or when the dying one goes out kicking and screaming (or with teeth clenched), what then?

And when we don’t have the privileges, adequate end-of-life care, or any kind of team rallying around us to have a so-called good death, what then?

I anagrammed the words “a good death” because that’s how I roll and as always, I was intrigued by the words that showed up. Godhead, Geodata, Goaded, Doted, Ego, Hated, Adage, and Oath were just a few of the words that leaped off the screen at me.

The geodata from a death and dying space is plentiful. Like birth, we can attempt to manipulate and contrive an ideal. We dote on the dying one and without realizing it, by the very ways in which we show up, we unconsciously goad and cajole them to do and be the model dying person — serene, peaceful, unafraid, inspiring. In other words, egos can loom large and things can get a bit selfish and even extractive.

Not surprisingly then, the dying one will often take their exit cues from those who hold vigil and from the emotionality that abounds in the grief container itself.

What I’m saying is that death as last act can be a performative utterance; a solo soliloquy wherein “the slant,” as John Updike names it in his poem “Perfection Wasted,” is “adjusted to a few, those loved ones nearest the lip of the stage, their soft faces blanched in the footlight glow, their laughter close to tears, their tears confused with their diamond earrings, their warm pooled breath in and out with your heartbeat, their response and your performance twinned.”

I’ve witnessed this more than a bunch of times, watching the nearly departed one defer to their family rather than advocate for their own late life needs. I remember having a conversation with someone dear to me in the months prior to his death. His main concerns were all about his family of soon-to-be left behinders. I nodded my understanding but inwardly, I was feeling all the feels with his selfless stoicism and compassion.

I said, “Yes, and don’t forget about you. This is your death. The more you’re true to you, the more you’ll be pioneering honesty and integrity in death for them.” I was doing the doting and goading thing, this I know, but we the living are so gosh-darn needy when it comes to those who are doing their level best to leave a sexy corpse.

It’s why I bristle at people thinking the dead need our “permission” to die. They aren’t looking for our permission so much as they need us to quietly back the fuck up, hold them in love, and give them the time and space they need for their life to unspool as it will, so their death can thread their soul through the eye of a new needle, which is to say, that ineffable portal to a great unknown.

Alas, death and the mere thought of it remains scary to us. Hence my affection for this quote.

“We continue to share with our remotest ancestors the most tangled and evasive attitudes about death, despite the great distance we have come in understanding some of the profound aspects of biology. We have as much distaste for talking about personal death as for thinking about it; it is an indelicacy … (yet) death on a grand scale does not bother us in the same special way: [ . . . ] It is when the numbers of dead are very small, and very close, that we begin to think in scurrying circles. At the very center of the (circle and) problem is the naked cold deadness of one’s own self, the only reality in nature of which we can have absolute certainty, and it is unmentionable, unthinkable. We may be even less willing to face the issue at first hand than our predecessors because of a secret new hope that maybe it will go away. [ . . . ] “The long habit of living,” said Thomas Browne, “disinclines us to dying.”

(And that’s because it’s) become an addiction: we are hooked on living; the tenacity of its grip on us, and ours on it, grows in intensity. We cannot think of giving it up, even when living loses its zest---even when we have lost the zest for zest.”

Lewis Thomas, from The Lives of a Cell

I’m not sure how I got on such a tirade.

I suppose it’s because the ceremonialist in me so desperately wanted to yell, “Cut!” and “MAiD Death, Take Two!…but with more tenderness in the tending this time!” during that deathbed drama sequence recently, even as I know that no amount of rehearsing is going to change the players, the family system, or the dynamics.

I say this thinking about someone I know whose parent died recently. Sadly, the sibling toxicity and shadow energy alone should have been enough to send this poor dying parent to their grave. I honestly mumbled, rest in peace when I heard the person had died.

You should know that I’m equally suspicious of notions of a good birth. Three miscarriages, including a traumatic stillbirth delivery, have taught me to look away from the shiny stories. Birth is a bloody miracle - no two the same — and so, too, with death.

Both death and the brave humans I’ve watched take their last breath remain my greatest teachers. Their final exhale, which is often the ragged sound of an agonal breath during a MAiD deathbed scenario, floats out upon the ether and nudges me back towards fiercer living and a more poignant perspective about life.

I was sharing with a friend yesterday that I’m more apt, following a MAiD death, to go out and do things I wouldn’t normally be able to stomach. In this instance, that translated to going to Costco on a busy Saturday before Thanksgiving. What fool willingly does that when they have nothing on their shopping list?!

Someone who just watched a person take their last breath and knows that physical health is a gift, that’s who. Lo and behold, if I wasn’t just a smidge more patient and generous in traffic and in the busy aisleways of Costco.

And I’m guessing that’s a bit of what Anderson and Tig were getting at in their chat about death doulas. Death consciousness awakens us to an ulterior path of living that Tig admits is a sweet spot and new normal. “I don’t want to get caught in anything that is not real.”

This, after hearing Andrea’s penultimate words, “I fucking loved my life!” and witnessing what assuredly was a transformative dying scene, begs us all to ask the Mary Oliver question of ourselves.

Am I breathing just a little and calling it a life?

(Note to self: am I?!)

To Be Alive

by James Crews

In every moment of grief, there is

a small opening, perhaps the size

of the hole cut in the birdhouse

hung on a tree in my neighbor’s yard.

It seems that nothing could thrive

in that tight, dark space, but soon

I see the flash of fledglings aching

for flight, yet still afraid of it.

And when the mother wren returns

with food, somehow fitting herself

through the opening, I hear

the chirping chorus of their hunger

to be alive, and standing alone

on the gravel road, suddenly

remember my own.from Turning Toward Grief: Reflections on Life,

Loss, and Appreciation (Broadleaf Books, 2025).

I love you so……

Ahhhh......I had to take a deep breath after reading your eloquent words. So much truth about how death, waiting for and planning for, death, being present at a death.... is such a complicated and dynamic situation. And one that affects every single person involved differently. You have captured this in a breathtaking way my dear Danna. Phew.